Let’s deconstruct what Obama said about the Caliphate…

My other pages

Archives

-

Recent Posts

Let’s deconstruct what Obama said about the Caliphate…

Myself, alone, in my bed, is a story.

Creature is a quiet place.

It’s deliberate, clean, and deeply personal.

Delicate too, and therefore deceptively strong. I imagine Amina Cain staring at a block of marble until the story takes shape. “Together the rocks formed a micro-climate for plants that grew in the shade I made.” This is Cain’s prose. Tendril sentences shoot up and form stories in themselves, wrapping around the text, growing from inside it.

Creature moves according to its own laws. Characters wash, they meander, they consider art. On the cover Thurston Moore compares Cain to the girl in the backseat, looking. I know what he means. Cain pays attention. He goes on, “That is how her thoughts and words make me feel, like clouds hanging with jets, and knowing love is pure.”

With prose like “Softly, softly the books” you’re floating through wide open spaces, fields of wildflowers, carefully arranged stone towers, then shadows drip across the text, four ornate wooden chairs staring at a whipping post, a girl being beaten by her lover, master, rapist.

A few weeks ago, a visiting Benedictine monk who was giving a talk in the dining room spoke for a few minutes about reading. I might get this wrong, but I think I remember him saying that in his tradition the word is supposed to send a person into the great silence. Just a little bit of reading is enough.

It is very easy to use Cain’s prose as a metaphor for Cain’s prose. That fascinates me.

Cain writes only what can improve the silence.

Immediately, she reminds me of Duras. Quoting Blue Eyes, Black Hair makes so much sense. Duras haunts you as you read her. She seduces you and it hurts. There is so much beauty in her darkness. Both Duras and Cain’s texts expose themselves so honestly that it feels like concealment.

The curtain moves, and I like the way it matches something inside me. But I know that a curtain shouldn’t match me, and that I shouldn’t like it.

There, too, is so much beauty in Creature’s darkness.

Without the traditional story structure cage, these stories are fertile, and feral. You can’t just demand this text dance and do everything for you. You’ve got to water the words, stop at the end of each paragraph and listen to your breath, then watch as the images flood. These stories are for you, they move inside of you.

Claire Donato had a similar experience reading Creature. Here is her review on HTMLGIANT.

Cain,

It’s hard not to feel connected to yourself when you’re in a hot bath.

and,

Like a creature that won’t get down from the bed, words are coming to me.

So simple, yet not plain language. She is not trying to get a point across as quickly and thoroughly as possible. This is a feeling she’s transcribing, a kind of sacred ritual, an ambiance, a mood. It’s as though she is your yoga instructor, guiding you through meditation. She treads softly, she rings the gong, where were you for 20 minutes? Transported, just as her characters become.

These characters are often writers, and as writers they experience visions, words happen to them. Suddenly narratives are becoming, they’re braiding, inhabiting each other’s spaces. In The Beating Of My Heart, the writer imagines an actress portraying her last heroine. All three of them speak. Perspective flows from one character to the next. I feel them as one. I read all her stories this way.

Except for the narrator in Furniture, Table, Chair, Shelves. Unlike the other voices, this one is unapologetically privileged. She feels like an intruder upon the text. She lacks the compassion of the others. The protagonist in Gentle Nights gets an aristocratic dress, she feels uncomfortable with it. That night she says, “We watch something violent on my laptop. It will help me wear this dress.”

Looking away from violence is to want to remain naïve. This is a luxury. An awareness of that takes the sting out of the garishness of fashion, but only slightly, and it wears off. When you are privileged, you have to constantly remind yourself that most of the world isn’t. To avoid this is to avoid what it means to be human and decent.

This is not easy. There are days, weeks when I want to avoid the news. When those youtube videos make me vomit and I become so violently angry or terrified or furious at myself and embarrassed because I’m terrified. The chemical attacks happened when I was nursing seven hours a day. At that time in my life I cried all the time. I cried because I was grateful, because I was in awe, because babies are fragile and strangers can be so kind. My body needed to gush, and when I encountered grief, my dams burst and I couldn’t stop. So I turned away. My husband and NPR could fill me in, but I couldn’t look at raw footage. Still, I struggle. My heart breaks every time. I become nauseous. #BringBackOurGirls #YesAllWomen Ukraine. Syria. This is the world we live in. This shit happens every day. #NotABugSplat

Cain is so painfully aware of that.

Awareness leads me to art. I need it. I need it to understand. To escape and to remember. I need it to shift and move me. I need it to teach me about myself. In Delicately Feeling the narrator tells a play she has just seen to fuck off. This is the appropriate reaction to art that disappoints you.

When literature speaks to you, in exactly the right way, you feel less critical of yourself. Less alienated. Less self absorbed. #BooksNotGuns It’s hard to imagine a racist, sexist, homophobic–or anything else equally stupid–bibliophile.

After friend breaks up with the character in Gentle Nights,

On the other hand it confused me, and made me feel as if I didn’t know myself as well as I thought I did, because I loved her and I believed I had shown her this in other ways. Maybe I’m not as in touch with the harmful parts of myself as I am with the loving.

This I know.

As the mother of destruction, I have little time to be in my head. My eyes are focused, and unless she’s asleep, one eye is always on her, because if it’s not, she’s standing on the dresser, licking a cheese grater, grabbing strangers’ shirts and yelling COLORS at them. When I do have an hour to myself, I want to be alone. My social life is miniscule. I read one book a month, 75% less than before Aria. I try to write as much as I can, but that suffers too. I have lost friends because of this.

Cain and I are very different writers. I am a messy writer, I write from my messy body in my messy home. I admire her cleanliness.

We do have this in common:

Sometimes I’m extremely frustrated when I write, and in moments I am extremely scared. I never knew it was possible to be scared while working on a story.

This is not vanity, not a fear of failure, or success, but a fear of the rush–of the magnitude of art.

Because inspiration emanates from within the body, and because I am a hypochondriac and fearful of my body, this rush frightens me. Inspiration hits like cocaine. It’s euphoric and stimulating but unlike cocaine the addiction never interrupts the moment; with cocaine, you’re always servicing cocaine.

Compassion and tolerance and curiosity grow in these pages. This book makes me want to be a better person. To throw out all my belongings and travel. To spend less time on the internet. To do yoga more regularly, eat less sugar, buy more plants, and calm the fuck down.

From the always wonderful Dorothy, a publishing project, Creature was fucking great.

Seriously, fuck this persistent trope of glorifying and preserving the innocent, pretty girl victim, and especially fuck the cultural obsession with “virginity.”

Virginity is a social construct. It is impossible to define without making it glaringly obvious that its perimeters are patriarchal in nature. Penis in vagina only, even “just the tip,” represents the loss of virginity. Absurd. What about LGBTQ? For starters. Gold star lesbians are not virgins, douchebags.

The idea that sex is something a woman gives a man, and she loses something when she does that, which again for me is nonsense. I want us to raise girls differently where boys and girls start to see sexuality as something that they own, rather than something that a boy takes from a girl. – Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Thank you.

And while we’re angry, fuck romanticizing young women killing themselves. (I’m looking at you Vice.) Beauty cannot be preserved in death. To age is not to ruin. We should not be teaching girls that being young and media-standard-pretty and nubile forever is better than living and changing and wrinkling and experiencing and thinking.

When my toddler sees an elderly woman decked out in jewelry, she stops and says, “Oooh pretty!” I don’t want her to ever forget this. It is the act of being beautiful that is beautiful.

Just like Girl, Interrupted, and Prozac Nation, The Virgin Suicides was an artfully shot, once book, dark girl movie from my teenage years. All of them are in debt to the inimitable Plath pandemic that plagues campuses across America. Plath was a tortured genius, and it’s unfortunate that all too often her words are overshadowed by her death. There are so many more, too. Hence the Vice photo shoot, but this is false, false, false, there are so many incredible women writers living, alive, shooting words from their palms. If you want to write, and you’re a woman, you don’t have to die to be taken seriously.

Don’t kill yourselves, ladies, make them take you seriously.

The Virgin Suicides GLORIFIES its “protagonists” deaths. They are each sad, blonde Snow Whites and Sleeping Beauties forever preserved in the minds of our narrators, a group of loser young (now adults) men who obsessively pore (are still poring) over all the details of the girls’ lives, any piece of the puzzle they could garner to make sense of the girls’ tragic deaths.

The movie opens with Cecilia’s attempted suicide. She’s in the hospital bed, her wrists bandaged. The doctor tells her how easy her life is blee blue blah. She then says, “Obviously, Doctor, you’ve never been a 13 year old girl.”

Promise! A story about the hardships of girlhood, not the trivial hardships that most pop culture idolizes (which is still very important, but in making it consistently trivial you are telling girls that they are trivial when they are everything but), but the existential crises all teenagers face.

Against their stupidly strict yet undefined rules which seem to come without real punishment, the parents throw a party for all their daughters, but especially for Cecilia. All the boys come because they’re all obsessed with the pretty flower vases with the blue eyes. The party is awkward. Until a young man with Down Syndrome shows up. The boys begin making the young man perform. The girls laugh. It’s gross and uncomfortable and it all makes Cecilia really kill herself, thus ending the party. I’m still on board, it’s the beginning of the movie.

I’m watching this by myself, with the kind of migraine that demands dark and quiet, something Sofia Coppola is very good at. I wanted to submerse myself in my girlhood: pink lava lamp, poetry written in blood, dried roses pressed in books, a rosary dangling on a picture frame, my teenage aesthetic, the dark girl from the suburbs. I remembered not liking the film then (whereas I loved Girl, Interrupted), and I wanted to remember why.

Well, there are no protagonists. The closest would be Lux, Kirsten Dunst. She’s the slutty one, though in the beginning, they’re all depicted as horny. Lux is the only one who acts on these urges. Awesome! Agency! Oh, wait, it’s bad, it goes badly. The hottest guy in school, Mr. Trip Fontaine, pursues Lux. He, too, falls in love for no reason, because she’s pretty. And that’s supposed to be like duh, because any boy who encounters the Lisbon girls and their waifish, white, billowy, gently wafting curtains personas, they’re ensnared, because that’s all boys really want, the dead girl in the glass coffin. Lux plays hard to get. So Trip thinks her father owns the keys to her sexuality. He doesn’t, the mother does. Trip asks Dad, Dad asks Mom, Mom agrees, but all the girls must go, so Trip has to find all of them dates, he does, it’s too easy as all the boys beg him to ask them because why would the rest of the girls get a say this is a male fantasy after all. All is successful and Anakin Skywalker is there too! Lux and Trip drink and make out then do it on the football field. HEAVEN, except NOPE they are abandoned by the rest of the party then Lux is abandoned on the field and has to find her own way home which she does and her parents are pissed and all the girls are taken out of school and the windows become quasi-boarded up. Okay…

Now, Lux asks random dudes from fast food places to meet on her roof where she fucks them and the dorky, obsessed narrator boys watch from across the street with binoculars and telescopes. They feel sympathy for Lux when the guy cums too soon, and they lament the cruelty of locking the girls in a proverbial tower. But they don’t do anything other than jerk off. Eventually they communicate via Morse code with lamps and telephone each other playing music because if I were a Lisbon girl locked in a house with crazy fucking parents and I finally found someone to communicate with and ask for fucking help, which is their first Morse transmission, I would want to listen to some Joni fucking Mitchell through the goddamned telephone.

Now, Lux asks random dudes from fast food places to meet on her roof where she fucks them and the dorky, obsessed narrator boys watch from across the street with binoculars and telescopes. They feel sympathy for Lux when the guy cums too soon, and they lament the cruelty of locking the girls in a proverbial tower. But they don’t do anything other than jerk off. Eventually they communicate via Morse code with lamps and telephone each other playing music because if I were a Lisbon girl locked in a house with crazy fucking parents and I finally found someone to communicate with and ask for fucking help, which is their first Morse transmission, I would want to listen to some Joni fucking Mitchell through the goddamned telephone.

And this leads me to my greatest beef: WHO ARE THESE GIRLS??? Literally, who are they? None of them have any distinguishable personality except Lux who is basically a quixotic slut who likes rock music. She has those three traits and that’s it, the other three have none. Her and Cecilia are the only two with personalities and speaking lines, the others are house plants. Their parents are nebulously, vaguely religious strict. There are no signs of abuse or neglect. The father is hapless, letting his crazy wife make all the decisions which seems to be solely based on a no sex policy because girls are flowers that need to be protected from evil boys out to steal their virginity and leave them in football fields. Because once a girl gets a taste of the naughty she’ll become wildly destructive and give it up all over town, which all happens to Lux. Yawn. This movie is a parable and it’s bullshit.

Why didn’t the girls rebel? The only punishment we ever see is that Lux has to burn her records in the fire and black smoke fills the house, everyone chokes, and this was clearly a failure and Mom gives up and merely throws out the rest. This scene is supposed to be heart-wrenching except it’s totally not. One, it’s just stuff, and while stuff is important to a teenager, so is school and freedom and both of those were taken away with nary a scuffle. We only see Lux protest each individual record for futility’s sake because music is life. Yawn.

Lux wasn’t afraid to stay out all night and fall asleep on a football field with kind of a stranger. She wasn’t afraid of her parents! But then, they took everything away and she cries for her records. She’s not like, FUCK YOU, MOM. IN TWO YEARS I AM SO OUT OF THIS MONASTARY. Which is the reaction I would expect of the girl who decides that on her only night out she’s going to stay out ALL FUCKING NIGHT like it ain’t no thing, like she’ll just get the proverbial slap on the wrist. Except she ruins her sisters lives and they all become princesses, pretty and passive, until they can’t take it any more. They ask the annoying narrators to come rescue them, and they do, they’ll drive anywhere, literally anywhere. They envision all sorts of trips from the travel magazines they steal from the Lisbon’s trash. “Cecilia’s not dead! She’s a bride in Calcutta!” they fantasize. Oh, okay, a child bride, that’s much better. Assholes.

They arrive at the house. Lux is all sexy and slinky and we’ll be out in one minute except nope because they are all dead. The end. Let’s venerate them and this behavior. Those pretty, pretty muses in their first Communion dresses. The perfect girl! Hymens in tact, unsullied. Stupid. Stupid. Stupid. Misogynist bullshit. Glorifying the unattainable, placing women on impossibly high moonbeams, denies them a chance to be people, just as the movie doesn’t make them people. The flowers died and I’m supposed to be sad but I can only be as sad as when I accidentally kill a house plant. It sucks, but plants come and go. They have no feelings, no desires, no agency. In the beginning, all the girls rub on their only male house guest like cats in heat. They give furtive glances. Then they don’t talk to anybody. They’re rude. Odd. In their own world. Which seems like an awesome sister world that I would’ve LOVED to see, to be a part of, but I can’t because this story is from the lovelorn male narrators’ points of view, which is to look and to awe and to circle jerk.

Maybe the book is better. Books usually are, but I know it has the same structure, is told from the same male gazing, so I’m not hopeful and I’m not wasting my time. My reading list is full and my time is limited. So yeah, fuck this misogynist claptrap. World, please stop stamping your boot on little girls’ faces. Let them speak. Let them shine. Don’t kill them because you think their innocent lives need to remain innocent and that that’s the height of beauty. Real beauty has scars and wrinkles and fat and stands despite being knocked over, despite being stepped on, and says, I’m still here, motherfuckers. I’m still here.

Virgin. Mother. Crone. The life cycle of a woman according to her lady bits.

Virgin. Mother. Crone. The life cycle of a woman according to her lady bits.

In Lynne Masland’s “The crone: emerging voice in a feminine symbolic discourse”, the crone is “an alternative symbolic discourse that permits women’s voices to be ‘heard.'” No men to impress, so close to death, she just doesn’t give a fuck. This is Baubo lifting up her skirt in Demeter’s grieving face.

In Diana Wynne Jones’ Howl’s Moving Castle, Sophie Hatter doesn’t have a choice, or a voice. As the eldest, she is to take over the hat shop, and if she ever were to “seek her fortune,” it would only bring catastrophe. So while Sophie is exploited in the hat shop, her stepmother gads and her sisters become sexy witches and bakers. Because of Sophie’s pathetic resignation, she is a plain, quiet, and hollow domestic person. Nothing.

Out of nowhere, the Witch of the Waste enters the hat shop.

BAM! Old age! And she can’t tell anyone.

I’m not afraid of getting old, it’s a privilege and a luxury, but I am afraid of unnecessary premature aging. The deleterious effects of smoking, weight gain, pregnancy, migraines, painkillers, hypochondria. I’m afraid immortality is only a century away and we’re all going to miss out. I’m afraid of wasting time. Bad structuring. Sloth.

There’s still so much work to be done.

I do love my graying hairs though.

Crones are usually harbingers of death.

Sophie hobbles to the rainy hills and settles herself inside Howl’s castle. More afraid of her immediate pains than of hearteater Howl, she makes herself comfortable in front of the fire, Howl’s fire demon, Calcifer, a falling star, now, the engine of the castle, Howl’s heart.

Here, Hayao Miyazaki‘s gorgeous adaptation splits from the book’s plot.

I’ll bounce back and forth between versions, but it’s no matter as the themes are similar.

And spoilers. Always spoilers here.

Sophie’s appearance now resembles her interior. Waiting for death, she withdraws from society.

Western culture doesn’t tend to find the crone all that interesting, barely ever one tall enough to stretch out of a trope. First, the negative clichés: she can be evil, like when the queen transforms herself into a hag to kill Snow White; she can be crazy, hurling bags of cats; or she can represent staunch morality (fucking Dolores fucking Umbridge), or a horrid super ego the heroine must shake off. Or, she can be the warm vanilla grandmother, or the wise earth mother, à la the Trash Heap from Fraggle Rock. Only the Trash Heap won’t be ignored. The rest stand as wallpaper, even mothers of middle-aged protagonists, wise then gone. Usually dead. If there’s a middle-aged protagonist woman and an elderly mother, one of them is going to die.

Western culture doesn’t tend to find the crone all that interesting, barely ever one tall enough to stretch out of a trope. First, the negative clichés: she can be evil, like when the queen transforms herself into a hag to kill Snow White; she can be crazy, hurling bags of cats; or she can represent staunch morality (fucking Dolores fucking Umbridge), or a horrid super ego the heroine must shake off. Or, she can be the warm vanilla grandmother, or the wise earth mother, à la the Trash Heap from Fraggle Rock. Only the Trash Heap won’t be ignored. The rest stand as wallpaper, even mothers of middle-aged protagonists, wise then gone. Usually dead. If there’s a middle-aged protagonist woman and an elderly mother, one of them is going to die.

Masland writes,

Because any image [of the old woman] is collectively created, it loses power and voice through indifference toward the topic on the part of the audience and writers.

As wallpaper, Sophie can blend into the background, Howl’s background, and make herself useful. She uses the trope to her advantage. She wants to be invisible, she doesn’t want to be heard, because all she wants to say is that she’s cursed, but she can’t. So she resigns to silence.

I also have a fear of not being listened to, not being taken seriously. It’s more of a neurosis. It stems from a severe distrust of the patriarchy. When I encounter the feeling I become enraged.

In Howl’s Moving Castle the crone is the protagonist, something precious and rare, but because Sophie isn’t actually old, she lacks the cliché windbaggery qua wisdom old people often exude. She’s aware of herself as wallpaper and sets about grandmothering Howl’s space. She cleans away the ashes in the hearth and makes sure Calcifer has fresh logs to eat.

Howl, Calcifer, and Michael–the child apprentice, had let the magical, moving house fall into shabbiness. Her maternal instinct is to make a nest. I wondered if Howl could detect Sophie’s pheromones, whether or not she ovulated, whether or not he could smell her eggs, or if she was an old woman through and through, or an old body wrapped around her young one. But these are questions one doesn’t dwell on in fantasy, especially YA fantasy.

In Miyazaki’s film, Sophie turns back into a maiden when she sleeps, though her hair has forever lost its pigment. In the book, to a few in the know, a sort of buzz emanates from her because of the spell.

Because Sophie is a crone, because she is wallpaper and “old” and “ugly” and “barren,” Howl cannot eat her heart, but we have since learned that gossip is gossip and that while Howl is narcissistic and histrionic, he is not evil. He only metaphorically eat hearts. He’s a coward. His house, a reflection of this, has four doorways that open onto four different locations, one of which being a different, magicless world: Whales, England, Howl’s home, our world; another being the steam punk heap in motion. (The other two are obviously locations inside Jones’ world.)

Again, Masland,

Because she is no longer connected with the reproductive economy, [the crone] has an independence and autonomy quite different from the status of the virgin or mother.

Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.

I once loved Janis Joplin. I still do, but differently.

As a crone, Sophie’s become openly honest and sassy. Howl is constantly pissing her off, but it’s all minor, and if it weren’t for her appearance it would obviously be flirting, so I so wanted it to be flirting. I read it as flirting. I wanted him to see through her curse yet in spite of it make love to her all the same.

This honest sass is Sophie’s rebirth. She left the hat shop because duh no one would believe she was Sophie so she reinvented herself as someone who leaves town, climbs into a moving castle, and argues with lethal lotharios. She’s still domestic, she’s still humble, but because she’s no longer a sex object, Howl listens to her. Masland thinks that the crone presents an alternative polyglot voice for women; a powerful, emerging voice of the other sex. So many untapped old lady characters, that, in this enlightened post-third-wave feminism, can be seen and heard as people because men no longer want to fuck them. It’s not great, but it’s progress.

I’ve slowly been crawling back to writing. Ryan got a job. My schedule is settling. I’m going to yoga. We’re still in debt, we’re still struggling for that perfect parent artist sleep balance. I was going to end by paralleling that it’s not great, but it’s progress. But really, it’s great. Money’s money. Aria’s awesome. Things are getting better. I’m going to yoga.

And in the end Sophie gets her man. Here’s a picture of her holding Howl’s heart, Calicifer (who is both a character and Howl’s heart).

Older women shouldn’t have to feel pressure to dye their hair. Silver is amazing.

In both the movie and the book she gets to keep that glorious hair.

This

This book blog post is not about Beckett at all…

The inimitable Lily Robert-Foley, best friend extraordinaire, wrote a book, m, that, while a text in and of itself, is more of a transmission: the revelation of, or commentary on the space between Beckett’s L’Innomable and The Unnamable, which was first written in French and then translated into English–Beckett’s native language–by the author himself.

In between these two texts beats the third text, which Lily describes as:

the space between translations: An invisible text that emerges from the rupture/conjunction of the languages. In the poems, the third text is treated as a creative space that produces text (writes, figurates, allegorizes, critiques &c.). In this sense, the following “poems”/“notes” may or should be considered a sort of translation or reading of the third text of Beckett’s novel. (Introduction)

Inside this third text the chasm beneath our feet rips open: it invites: l’appel du vide.

At best, here, I offer my interpretation, my translation of Lily’s translation of Beckett’s autotranslation.

The whole point of this blog is to collapse the space between reader and text. To expose the reading process. This is what Lily accomplishes in m.

Like a road, or a poem, m is a metaphor. This is an experimental book of poetry, so the page can be intimidating, especially if you don’t speak both French and English, as she quotes Beckett in one language then gives the equivalent passage in the other, after which she then performs an exegesis, mostly in English, but also in French. Her words are ghostly, printed in gray (Beckett’s are in black). They give the illusion of hovering between the texts, as though she were reticent to pin them down, because they don’t belong in a book, they belong to The Unnamable, the texts: L’innomable/The Unnamable; but also as a concept: that thick, viscous, nebulous abyss that is everything and nothing. But even still, that’s not right as the third text deconstructs the stuff of the unnamable.

The third text:

does not locate the [third text] in an unnamable space but tries to determine the matter or substance of the unnamable, divide it, bust it, burst– (160/383)

But my understanding is that zero multiplied by anything will always be zero.

This is also what I mean when I say that I struggle with nihilism.

It’s all Zeno’s Paradox to me.

The ideal of the unnamable or the untranslatable refers to language that has no other, either because it is no language or is only language. The 3-text reading (a poetics of self-translation) is the confluence of these poles, or rather renders them irrelevant (since they are the poles of language-that-has-no-other in a system of language based on same/other). (74/331)

All thought is made up of language. To quote Wittgenstein: “The limits of my language are the limits of my mind. All I know is what I have words for.”

Now, what about the fact that I only speak English?

The text is already bilingual, even if you only read half of it. Holes where the other half of the text comes through (removable discontinua). The penetrable intimacy of language, or queer the gender, its enveloppable intimacy. It’s pour, poor, pore, porous, aporia. Like this book, some things you might not understand because they are in another language or situated in an obscure discourse, but it’s ok, like a self-translated text, you only read half, no text is a totality anyway. (90/340)

Language is gendered, it’s phallogocentric. Meaning, meaning tends to privilege the masculine: the throbbing, glittering Signifier.

Derrida’s deconstruction of speech and writing is bound to the word parole (untranslatable as speech). Parole is fatherly. Straight, from the soul, pure breath of spirit. (31/305)

Also, language is heterosexual (it’s all about the binary, baby). And holy. It is our most sacred tool.

To quote Sappho: “Although only breath, words which I command are immortal.”

Once upon a time, words were considered “truths.” There was no difference, no space between signifiers and what they signified. Deconstruction has taught us that language is a game of différance. Language is slippery. Words have meanings only because other words have meanings. Something only is what it is because of what it is not. These small differences make up the constellation of words and meanings, which means, no word can contain any essential meaning. Language is empty. Meaning will always be deferred through an endless chain of signifiers.

If this sounds confusing, translation only compounds the complexity.

The third text reproduces the rapports de signification internal to one language, but splays (écart) them out across two languages. Each language acts as a set of signifiers representing the other set of signifiers as their signifieds, and those signifieds acts as signifiers signifying the other set of signifiers as their signifieds. Endlessly, hall of mirrors, referring to each other. (30/305)

The third text is not gendered (from here on out, like Lily, I shall refer to the third text as “3ext”), it’s monstrous, “something so horrible I can’t put it into words.” Immediately, I think of the familiar yet foreign monster lurking in the apparently boundless basement in The House of Leaves. That entire metaphor, for me, is a metaphor for the divine and uncanny 3ext.

Familiar yet foreign:

Repeats, ça me dit quelque chose (literal traduction: that means something to me = ring a bell…)…

an in-between space that is also rhetorically beyond, too far, too close. (177/393)

The 3ext is always foreign to itself, a refugee, never at home, forever invaded, a colony of a state that doesn’t exist, where the native is the mold of the foreign. (181/395)

Or more succinctly:

The poetics of self-translation is the becoming foreign of the native and the rendering native of the foreign. (46/314)

The reason I’m quoting so much, and mostly quoting passages that “define” the 3ext is because once you’ve grasped some basic understanding of this space, this space stolen, as it were, from Beckett, you can fly with Lily through her poems, which are not as complicated as this blog would lead to you to believe: they’re playful and they’re funny. And yes, while Beckett is funny (think Patrick Stewart’s and Ian McKellan’s interpretation of Waiting for Godot, which was hilarious), this “book is not about Beckett at all.” It’s about the 3ext and it’s about Lily: the author: the author who was the reader, who translated back and forth, and quips: “Negligent writer seeks cop editor.” And, “the opposite of madness is raisin.”

Now, indulge me: “raisin” is obviously a pun on “reason” and more poignantly the French translation of reason, “raison.” But on top of all that, a grape can survive one of two ways, it can either become wine or a raisin. A raisin is wine that never was. The god of wine is Dionysus, who also represents pure madness. If wine is madness, then a raisin would be its opposite. Wholesome kids’ snack versus bacchanal orgy. Clever, and fun if you’re a super nerd like myself and love unpacking seemingly random symbolism to stitch together some type of chaotic whole that nurtures as it’s digested.

The text of m is hysterical, it goes from one subject to the next. To the reader, it’s as though she pulls a random Beckett quote from the hat then creates a palimpsest on his words. She inserts herself. Fucking the space between, the now stolen space between, Beckett’s work becomes othered. We forget that she’s siphoning off of him because she’s not parasitic, she’s a pioneer, as all us thinkers and readers are, but she’s literally marching through the frontier, conquering it, and passing it along. Herein lies the oscillation between hermeneutic discourse and poetic discourse. Lily once said that there is nothing more transgressive than to interrupt/surprise the father in the speech act. Herein lies another metaphor for the 3ext as Lily is constantly interrupting Beckett.

Good thing the author is dead.

But let’s not go there.

Long live the author!

(Especially Lily.)

Let us fly:

the meaning, value, weight, comes together while the material, phonemes, morphemes, choses, pull apart, as in the making of mountains : desire, love, reaching out to the other, Michelangelo’s Adam, bigger on the inside than on the outside : an analogy of infinite regress in ethics : the more I know you, the more mysterious you become to me, the more what I thought was my knowledge of you is eclipsed by my love for you : (132/366)

Wait! Bigger on the inside than on the outside?

Oh, the politics of interiority versus exteriority!

Boundaries are for suckers.

To explore the space of the self is truly the final frontier.

Speaking of…

Today Anaïs Nin would’ve been 111.

Let’s look at a full “poem.”

« Mais lessons tout ça »

« But enough of this nonsense »

Let’s leave, move away from, this language that doesn’t mean anything, go towards sens, follow a road full of metaphor, Jiji. (62/324)

Jiji is the eponymous character from Lily’s roman à clé, Jiji (forthcoming from Omnia Vanitas Review), which, though loosely autobiographical, is also an experimental ride, written progressively in code, so that by the end, the text appears unreadable. Because so much of the love story is lost in the translation, because one can never truly know the Other, because this story needs to be encoded in order to be told.

But inside m, the reader is not privy to Jiji–not yet–so the reader may not, and probably doesn’t know of Jiji, because they aren’t coming to this book of poetry with my perspective of privilege. Remember: “Like this book, some things you might not understand because they are in another language or situated in an obscure discourse…”

When the author others herself, who is reading? So here, the subject writes herself as other-object. She makes the her-in-the-page perform, read, translate the emptiness that creation can eradicate. Suddenly all characters are water. This can happen at any time. I love that about her work. This is Lily. She mostly writes ergodic literature; “nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text….[T]he reader…must participate actively in the construction of the text.”

Experimental, ergodic, hysterical, wonderful literature.

Since the 3ext resists organized hermeneutics, I will just leave you all with this aphorism:

Facebook is phatic-phonetic, has replaced main street the way television has replaced the novel. (110/352)

Then, because I love her, and I want you all to love her, I’ll leave this, then leave you:

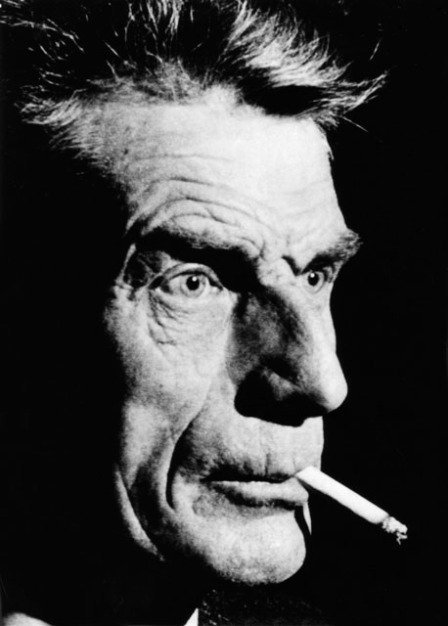

In preparation for reading my Lily Robert-Foley’s m –– which is a poetic translation project focusing on the third text between Beckett’s autotranslations of his trilogy –– I’m reblogging an old Beckett post I had once written on the slipperiness, falsity, and uncertainty of language.

Or… How Beckett Became Beckett by Abandoning Beckett.

Passages, and notes from Beckett and Bion by Kevin Connor.

Samuel Beckett and Wilfred Bion. 1934. Beckett was 27, Bion was 6 years his senior.

Samuel Beckett and Wilfred Bion. 1934. Beckett was 27, Bion was 6 years his senior.

Beckett left Bion in 1935 and completed Murphy.

It has been said that these two were “imaginary twins” because they were both concerned with the possibilities of understanding and communication against the background of psychotic denials of meaning and human communication.

The originality of Beckett’s narrative writing derives from the attempt (unacknowledged and probably unconscious) to transpose into writing the route, rhythm, style, form, and movement of a psychoanalytic process in the course of its long series of successive sessions, with all the recoils, repetitions, resistances, denials, breaks, and digressions that are the conditions of any progression.

We may say of Beckett’s analysis perhaps what Bion says of the material uncovered by analysis: “In the analysis we are confronted not so much with a static situation that permits leisurely study, but with a catastrophe that remains at one and the same moment actively vital and yet incapable of resolution into quiescence.” In other words, the repetition of trauma. Usually because one cannot understand their own death, or birth[1]. So in order to understand one repeats these traumas, or traumatic images, as a mechanism of coping, but really, just reliving.

Traditional psychoanalysis functions like a nineteenth-century inheritance plot, in which the forward movement of the narrative is defined by the desire to retrieve the past, and this forward movement culminates and concludes with the reappearance of that past, the kind of analysis proposed by Bion would inhabit the looped, interrupted, convoluted duration of the modernist or postmodernist text, in the form represented by Beckett’s Trilogy.

While Beckett was writing the Trilogy, Bion was working on his Attack on Linking of the second “psychotic phase.” Both works explore the experiences of negation and negativity. Bion reports on patients who display in their attitude towards the analyst and the analytic session a hostile inability to tolerate the possibility of emotional links. The essay begins with taking the “phantasied attacks on the breast as the prototype of all attacks on objects that serve as a link and projective identification[2] as the mechanism employed by the psyche to dispose of ego fragments produced by its destructiveness.”

Under these circumstances, the failure of the link constituted by projective identification then gives way to an angry denial of the link by the patient. Because the mechanism of splitting keeps open the possibility of a relation to what is split off, it is the activity of splitting that is thus itself denied. This can only take place through the primitive process of the original splitting.

In The Unnamable, this process of disidentification becomes both more urgent and paradoxical. The speaker begins by claiming that he will do without projective identifications’ imminent extinction: “All these Murphys, Molloys and Malones do not fool me…They never suffered my pains, their pains are nothing, compared to mine, a mere tittle of mine, the tittle I thought I could put from me, in order to witness it. Let them be gone now, them and all the others, those I have used and those I have not used, give me back the pains I lent them and vanish, from my life, my memory, my terrors and shames.”

The speaker discovers that to dissolve, or attempt to dissolve these phantoms, is to reintroject them. The analyst is involved in this process since he is called upon to play the part of the mother prepared to introject the negativity projected into her by the anxious child. If the mother comes under attack so does the analyst, and the process of analysis itself. The particular form which this attack often takes, Bion suggests, is an attack on language as the medium of symbolic and cognitive linking.

The possibility that Beckett’s own discontinuation of his analysis was associated with an attack upon language is suggested in a letter he wrote to Axel Kaun months later: “It is indeed becoming more and more difficult, even senseless, for me to write an official English. And more and more my own language appears to me like a veil that must be torn apart in order to get at the things (or the Nothingness) behind it. Grammar and style. To me they have become as irrelevant as a Victorian bathing suit or the imperturbability of a true gentleman. A mask. Let us hope the time will come, thank God that in certain circles it has already come, when language is most efficiently used where it is being most efficiently misused. As we cannot eliminate language all at once, we should at least leave nothing undone that might contribute to its falling into disrepute. To bore one hole after another in it, until what lurks behind it – be it something or nothing – begins to seep through; I cannot imagine a higher goal for a writer today.”

The struggle against language is identified with a struggle against a series of mysteriously oppressing tyrants, whose motivation appears always to be to force a coherent ego or human nature upon the speaker of Beckett’s fictions. These figures begin Molloy, to the one who demands Molloy’s narrative, and progress through to the tyrannical Youdi and his agent Gaber, who extort Moran’s report; and harden at last into the figure of Basil/Mahood and the “college” of tyrants which the speaker in The Unnamable evokes at various points through his monologue.

He then turns on and others (splits) his own body. He represents his language in bodily emissions, he grounds himself in the muck of mammalian existence. Bion sees such processes or phantasms in psychotic patients as an intensified form of splitting, in which undesired or uncontainable feelings and ideas are not so much fragmented as pulverized. All abjections become bad. For the speaker in The Unnamable the process of logorrhoeic outpouring is the reflex of a process of unwilled introjection.

The terms of Beckett’s fictional verbal-corporeal economy in The Unnamable perhaps sums up some of the features of his own psychosomatic suffering, or the sufferings he was persuaded to see as such. Beckett’s own boils, cysts, and dermatological lesions led him to seek psychoanalysis, they also suggest the importance of the relations between contained and container. A Bionian interpretation would suggest that the pulverization and moralization of the ejected contents of the psyche seek a form or receptacle. It’s as if Beckett’s psyche collided with his body, and this kind of representation excited Beckett, as is apparent with his grotesque characters in the Trilogy.

As a text full of grotesque bodies, it is uncertain whether or not “the speaker” truly is alone, trapped inside his mother’s womb, or speaking with two even more grotesque figures. What is certain is that “the speaker” is at the heart of the narrative, and that whether or not these creatures (Mahood and Worm) are real or imaginary, he is never alone because he has othered his own body.

I think, the solipsism of the Trilogy derives its energy from alterity, its otherness. The aggressive purging of the other from the self reveals that the self will never glimpse or grasp itself except through the openings of its inauthentic others. “The battle of the soliloquy” as Beckett described it, is a battle with and against these others, a speaking to oneself via their speech. Like psychoanalysis, it demonstrates “How little one is at one with oneself” (in Moran’s words) as both Beckett’s and Bion’s final works show, it is a battle that is played and won, or successfully lost, but only and always in company.

[1] Late in the analysis, Bion suggested to Beckett that he attend a series of lectures being given at the Tavistock by C.G. Jung. In the lecture, Jung spoke of the mechanisms of splitting and dissociation within neurosis and psychosis. There he told the story of a young girl afflicted by premonitions of death who, Jung said, had never properly been born. This haunted and fascinated Beckett.

[2] The term comes from “Evasion by Evacuation” by Melanie Klein: projective identification’, which Bion defines as “a splitting off by the patient of part of his personality and a projection of it into the object where it becomes installed, sometimes as a persecutor, leaving the psyche from which it has been split off correspondingly impoverished.”

Meg Wolitzer wrote an acclaimed, lauded, best-seller, The Ten Year Nap, which, in a nutshell, delivers what it promises. (Haha.) Her characters are all stay-at-home moms who were once promising in their careers but left them for one reason or another for early child rearing. Now, their children have grown, they’re not needed as much as they once were, and the mothers are left with the shambles of their personal and professional lives. The novel begins with all the women waking up, an obvious metaphor: Who am I? What have I become? What am I doing with my life? Am I happy? To answer: no one, nothing, nothing, no. I found this novel boring and I found a great many of the characters chokable. (That’s not to say that I didn’t identify with all of them (in a way).) This novel honestly portrays the choice to stay home, but even more to the point, it does raise some very important questions concerning feminism today. So let’s descend into the Mommy Wars.

Meg Wolitzer wrote an acclaimed, lauded, best-seller, The Ten Year Nap, which, in a nutshell, delivers what it promises. (Haha.) Her characters are all stay-at-home moms who were once promising in their careers but left them for one reason or another for early child rearing. Now, their children have grown, they’re not needed as much as they once were, and the mothers are left with the shambles of their personal and professional lives. The novel begins with all the women waking up, an obvious metaphor: Who am I? What have I become? What am I doing with my life? Am I happy? To answer: no one, nothing, nothing, no. I found this novel boring and I found a great many of the characters chokable. (That’s not to say that I didn’t identify with all of them (in a way).) This novel honestly portrays the choice to stay home, but even more to the point, it does raise some very important questions concerning feminism today. So let’s descend into the Mommy Wars.

Wolitzer has said that she in no way wanted to judge or promote one particular side. She just wanted to write a novel about high powered, smart and talented women–upper class white women–living in New York, who decide to forgo “it all” and raise their children. Many, including myself, do not want to place their babies in daycare. 3 out of 4 of these women are in a place where they can afford to live off one parent’s salary. In mine and Roberta’s case, whatever job we could get with our MFA degrees is not going to cover the cost of daycare, and keeping one parent at home is actually more feasible. I’m not against daycare, but I am happy that I was able to spend my daughter’s first two years at home with her.

In The Ten Year Nap, these women are miserable, pathetic even, some are basically children plugging their ears when they hear something unpleasant and are too afraid to even open the bills. Rather than becoming domestic queens of their domiciles, they’re reduced to whiny ash. Their dreams, once bright and open, have decayed into bitterness. They wake up realizing that they’re failures. (Not with their children: they’re happy, growing, flourishing even, but we get the impression that this doesn’t really matter, is beside the novel’s point. Not wanting to take a side, indeed.) We don’t get to see those early sleepless diaper strewn days. We see them with oodles of free time while their kids are at school. We see them sitting and bitching at the diner, attending job interviews for their own sake (since, miraculously, they’re often offered the jobs but never take them. In what economy, I ask? The economy right before the financial collapse…), and just generally moping and hanging out with their friends. The painter doesn’t paint. The writer doesn’t writer. The number cruncher, the happiest one, crunches numbers but not for money, and our ipso facto protagonist, Ms. Amy Lamb, is the worst of the clique.

Amy’s mother is a flag-waving feminist. One day she woke up, saw that her lot was bullshit and started holding consciousness raising meetings with other dissatisfied women. She followed her passion and became a successful novelist. She fought, she paved, and now she quietly disapproves of her daughter’s lifestyle choices, but she stays out of the novel’s limelight for the most part. I wanted more, but I always want more of the grit, more of the real. More of the Freudian.

I wanted the ladies to really jump into the rabbit hole of their depressions. I wanted to see their raw, dark, sexual, desperate sides. I wanted warts and all. Instead I got a general graying of feeling. Everything became tainted in meh.

Wolitzer’s observations, however, were poignant. Men today are helping more with child rearing. They’re changing diapers, walking kids to school, helping with homework, all that jazz. However, there’s still an imbalance. Men are far, FAR less likely to stay home with the kids. Society puts too much pressure on them–pressure to work and succeed–that they couldn’t even conceive of dropping out. They also, because inequality is still rampant, make more money. It makes sense for the lesser earner (and the “natural nurturer” and the food supply…) to stay back. Also, many men just find kids boring. (Those assholes who want to make ‘em but then have so little to do with them.) Here, the husbands are saintly but kind of dopey. But most importantly, they’re all bankers, lawyers, or corporate sharks. Except for Roberta’s husband. I couldn’t get past their social status, but they’re supposed to be Joe Six-pack. Because all men are alike. Amirite, ladies? Men be stooopid.

How many times, someone remarked, had you seen a man pushing a stroller, and then you looked down and noticed that the baby was wearing only one sock. “Wait up! Wait up!” a female passerby would call from farther back from the street, running toward the man and child with the teeny rogue sock in hand.

But such characterizations weren’t accurate, someone else said. And even if they are, the deficits weren’t fatal. It wasn’t as if these men would take their children out naked in the winter and drop them in the woods. It wasn’t as if they would starve them. But the husbands they lived with were part past, part future.

She then goes on to say the thirty-something year old husbands were so lithe and beautiful staying at home with the kids while the wives worked. HAHAHAHAHAHAHA. Sure, some, but oh my god, not enough to stamp it equal. This novel is considered funny, but often, like tawdry newlywed game jokes, the humor lies in pointing out insufferable gender stereotypes.

So boys, in their wildness, were simple, and girls, static and contemplative, were complex. Boys ran and ran, and then, when they were eventually tired, they sat and took things apart and put other things together, while girls quietly braided friendship bracelets out of little snippets of colored thread and gave each other the chills and promised lifelong fidelity.

As we’ve discussed, gender works on a sliding scale. Girls often feel forced to sit quietly and create while boys get to be boys and are encouraged to build, demolish, and run amok.

The deluge of pink alone! Pink, the color of submission and docility. Cops paint drunk tanks pink to limit the fighting, and it works. Don’t tell me society doesn’t love little girls sitting quietly braiding hair.

The humor lies in the cynicism, but I was often confused whether or not Wolitzer was critical of the way things are or championing them. If the former, then the whole book is satire but told without irony. Or is Wolitzer just a witness? Like any deft novelist tackling a controversial topic, she steers clear of definite answers, but she does show the boredom of the women in their gender-specific role, and the fatigue of the men in theirs. It’s not fair that the men have to slaughter the pig and bring home the bacon. But what really wasn’t fair was that once upon a time women weren’t allowed to do either of those things. Now they can, but some don’t, and third-wave feminism says that’s okay, but is it?

Elizabeth Wurtzel says no, and it kind of feels like a response to The Ten Year Nap.

The woman in 14F from Amy’s building had to move out of her expensive apartment because her husband dropped dead. That woman, who gives Amy a great deal of anxiety, depends on her husband, just as Amy does, just as all the women do. And then what happens if they were on their own? They’d have to go back to work, which, spoilers, most of them do in the epilogue, but until then, they all struck me as lazy. THEY’RE CORPORATE BANKERS’ WIVES. They get to choose to do nothing, complain, and look the other way while their husbands destroy the planet and the middle class. And voilà, their lives lack meaning. So Amy tries to locate meaning in a “friend’s” love affair (a fantastically insipid subplot), and in being morally superior to her husband and a slew of the other mothers.

Onto Margaret Thatcher, a small play within a play. “No one in skirts could get anywhere in today’s society without a spine. You had to speak with hard, unfeminine edges and in carefully constructed paragraphs, and if your listeners’ interest began to flag, then you had to do something about it, perhaps metaphorically birching the lot of them.” Is this still the case? Do women have to act like “men” to get anywhere today? Can’t women carefully construct their paragraphs without switching genders? Or do all women speak as Iriguray says, circularly, touching back on topics? Are all women maternal? Are we all fluid, preferring to bend to space rather than occupy it? OF COURSE NOT. Any suggestion of essentialism is ridiculous. Just as calling placenta eating a myth, and claiming that any woman who did practice it was giving feminism a bad name. Why? Because it’s gross? Because it makes these characters uncomfortable? Because it’s a form of radical motherhood? Or because it’s supposed to be a droll remark?

But these cynical, droll remarks add up. These women are judgmental, unhappy, unfulfilled, hating on their roles, blaming husbands for not contributing more to the child-rearing pot, but THEN THEY DON’T DO ANYTHING ELSE THEMSELVES (except for Roberta, an ex-artist, whose husband is also an artist, she volunteers her time driving underprivileged girls in rural areas to get abortions). Just a bunch of caddy, complaining, useless bitches. I’m being harsh but I don’t care. I hated them all. Not because they are stay-at-home moms, but because they are judgmental and rich and BORING. I think Wolitzer doesn’t like them either. I think she judges them too. I see it in the prose.

On the morning of the first day back to school after Christmas vacation, the first snow fell upon the city. From the windows of their financial and legal towers, men and women peered out upon the natural phenomenon. The men thought of sleds and of their children and of being a child. And from those same towers or their apartments or the warm light of the small shops that lined the avenues, more than a few of the women wondered if their children’s boots from last year still fit. The men thought of freedom, and the women thought of necessity.

The underlining principle I took away from The Ten Year Nap, was that without women, nothing domestic would get done, therefore, we’re not equal. Women had to stay home or they had to work and still do all the cooking, cleaning, cuddling, diaper changing, comforting, parenting. Of course they would opt to stay home. It was easier, easier than fighting the front lines of domesticity. Men were big kids after all. They’d eat nothing but Chinese take-out or cold soup out of cans if it weren’t for their wives. This, of course, is an exaggeration, but it does wear a shade of the uncomfortable truth.

Also, many women want to stay home.

Anne-Marie Slaughter tackles this in her much-buzzed article: Why Women Still Can’t Have It All.

Wolitzer wanted to write a novel about affluent, successful women who choose to stay home. She wanted it to be acerbic, honest, but it’s ultimately dull. She wanted to wake these women up from their ten year naps (as their children are ten) and have them look around and see just how useless their lives have become. They used their kids as an excuse to stay static, but see, girls like to be static, remember? Boo. Hissssss.

What I would have preferred would have been a book about Amy’s mother and her feminist friends. They have that deer-in-the-headlights can-do fighting spirit mixed with the perfect amount of naiveté and rage. They’re the grandmothers you wish you had, and they make excellent, depressing, and irksome points.

“I am willing to accept that the young generation is moving on in and dictating the way society will live,” said Betty Jean, a woman in a corner of the room. “Morality is not a cause I feel I can take on. Although, as a political progressive, I’m used to losing almost all my battles.” The women nodded in sympathy. “I follow every single story about injustices toward women, and there are plenty,” Betty Jean continued. “But what with fundamentalist Islam and the threat of terrorism, it’s gotten even harder to get anyone to invest their energy in this. It’s as though there’s just so much political interest most people can sustain. It’s like that game Scissors, Paper, Stone. Terrorism is ‘Stone’ now, and feminism––along with everything else––is ‘Scissors.’ Terrorism wins.”

This made me think of Simone, and how she says that a great reasons women’s rights never rose was because there is always some other cause “more important,” some other cause dividing the women up, and gobbling the men’s time.

Some say feminism died a long time ago. They say no one’s mad anymore. The “Me Generation” is too narcissistic and apathetic. They say they’ve hit the glass ceiling and are floating up there, all meek and unwilling to shatter that shit. Some say, the world is crawling with feminazis (a word that literally equates fighting for gender equality with genocide) and that there’s a war on white men.

I read this for my feminist book club, and us too, our conversation moved into politics, but that’s a testament, I think, to the book, and not some ingrained hierarchy. I learned nothing new from The Ten Year Nap. There were many times where I thought, Huh. I’ve noticed that! But then I almost immediately began fantasizing about food.

I’m reticent to publicly delve into Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy because I want to resist coming out of hiding. I’m in a period of drastic change. Change catalyzed by an admission of failure.

Things aren’t going well, they haven’t been going well, so I withdrew, submerged into the bioengineered world of Atwood’s speculative fiction. I lived in the aftermath of a meteoric airborne plague that just about completely destroys all of humanity. The setting is mythic. Kudzu everywhere, bursting through concrete, squeezing, choking, collapsing buildings. Seriously dwindling resources, as most of civilization has already been looted, destroyed, or contaminated. Gene-spliced animals seem to have overrun their more docile kin: deadly liobams (lions crossed with lambs), bunnies that glow an unnerving ethereal green, pigs capable of symbolic thought and gesture.

What I liked best about the MaddAddam trilogy is the slow reveal. How the entire narrative beats in exposition. There’s tension in the past, but when you know that everything, all life, the world, everything, is about to COMPLETELY change, the action is tempered. The setting is the star of the show, and in no way does that suck.

The plague, or the Waterless Flood (as it will be referred to as later), was created by a genius twenty-something to rid the earth of the stupid humans. He injected the virus into a pill, a kind of vitamin, that promised bliss and sexual healing. Everyone turned to goop, except for a handful of protagonists, some of them bioengineers, a lot of them strict spiritual vegans, in the sociopolitical sense. They were outlaws. I wanted to be among them. Growing mushrooms in some basement, raising gardens on rooftops, chasing away pigoons and wearing bedsheets to block the sun’s magnified radiation. Foraging, defending, building from scratch, all seemed easier than finding work in a recession, and eventually, even doing the dishes. I knew this feeling. I knew it well. I was depressed.

About a month or so ago I stopped taking Nortriptyline, suddenly. I know, one is supposed to taper, but I was impatient and wanted to feel something, even if it was brain shivers. It wasn’t nearly as bad as when I quit Effexor, which I did taper, breaking open pills and counting out beads even, but still, it wasn’t great. My migraines increased, as did my Vicodin intake. My neurologist left the state and her replacement wants me off all medication, except for another migraine preventative, Nortriptyline’s cousin, Protriptyline, and the occasional sumatriptan. I’ve been on Vicodin for nearly seven years. I’ve killed my body’s natural dopamine receptors and my endorphins run dry. I no longer know how to fight pain. Radio Lab recently had an episode about a guy who couldn’t eat for years. His taste buds died. His tongue was flat and pink and completely bald. I can’t help picturing that image.

Oryx and Crake begins with Jimmy, who is not doing so well. He has changed his name to Snowman, thinks he’s the last human on earth, is only alive because he is responsible for the Crakers, beautiful humanoid creatures invented in a lab, by Crake, Jimmy’s best friend: the boy genius responsible for the plague. The story follows the cynical Jimmy through his mooning and his failings. I identify with Jimmy because I’m in a period of self-hatred. I feel just as ridiculous and out-shined, but Jimmy suffers from unrequited love, at first with a picture, then with the equally unattainable girl in the flesh, Oryx. He thinks he’s an emotional cripple, and he is, in a way, but nothing a healthy relationship couldn’t fix. But one wonders if Oryx experiences any emotions at all, or if her emotional receptors run as dry as my dopamine. She has seen hell, and it’s partially because of this sheltered Jimmy loves her.

Jimmy only knows compound life, as opposed to pleebland life. Think of 1984’s party life versus prole living, except this isn’t a dystopia based around a political ideology. Though Atwood’s CorpSeCorps does retain the iron fist, that closing in feeling, MaddAddam’s world centers around mass extinction. To compensate, scientists within the compounds are perfecting synthetic living from growing insurance organs inside pigs (pigoons), to chickens without hearts or brainstems (doesn’t KFC already do this?), to sheep-like creatures with full heads of human hair, etc. As I said, the trilogy, for the most part, is entirely exposition, which is great, but to Jimmy, nothing is happening. He watches a lot of porn on the internet, and executions, and he plays complex computer games, has little human interaction.

Jimmy and me both were suffering from ennui. I had writer’s block. I hated my sheltered past. I felt boring. I don’t see my friends as much as I’d like to. So many of them are doing great, interesting things, and I felt they were passing me by. I felt isolated as a mom. I was getting used to only talking to Aria or about Aria: she’s trying to write now! She’s leaping off the trunk onto the bed! She said camel! Moms who only talk about their kids are boring. When I go out into the world, I feel invisible. I look tired. I look in the mirror and I don’t recognize myself. When I write, the process takes too long. Pages used to flow out of me, now it was taking me hours to write a couple of paragraphs. I lost the flow. I even started questioning my sacred space, my parenting skills: was I giving her too much TV? Why isn’t she eating anything? Am I imprinting depression onto her? In short, I’m a piece of shit who cannot produce her own dopamine.

Atwood is famous for The Handmaid’s Tale, which is another dystopia: a misogynistic, religious horror story. The Tea Party’s wet dream. That world, too, was vivid and penetrating, but now it seems sparse to me, its yarn was ideological, terrifying, and rage-inducing. In The Handmaid’s Tale, you drown. Inside the MaddAddam trilogy, you swim. You don’t feel like fighting or fleeing, you just wait for the inevitable, then survive it. The angry period is over. Climate change has destroyed the planet. Everything’s dead. First the plants and animals, then the people. Sounds good.

I had this overwhelming sensation that the world is fucked, that with climate change it’s too late, that violent tragedy is around the corner, that the jobless recovery has widened the class gap so far, I can only see us slipping further into poverty. We can’t afford nice things for Aria. Groceries are too expensive, but I am clinging to those fresh vegetables for dear life. I’m still struggling with my weight. Just the other day the cats peed on one of the only jackets that fits me. I couldn’t handle it. I was angry all the time. And sad. How do I stop hating myself?

“To stay human is to break a limitation.” Oryx and Crake.

In The Year of the Flood we switch protagonists. We move onto Toby, Jimmy’s opposite: hardened, wise, understated, quiet, dignified, level-headed, and stoic. You can tell she was written with admiration. We also follow Ren, a child when she lived Toby on the Edencliff rooftop as a fellow gardener, but now, in her late-twenties, she is locked inside Scales and Tales, an upscale brothel, while Toby has bunkered down inside the AnooYoo spa. Much like Oryx and Crake, much of this novel flashes back to life before the Waterless Flood, life before Crake destroyed it. Still laying down the setting, spinning and spinning, we start to see past the compounds, past HelthWyzer, OrganInc, and RejoovenEsence. The Year of the Flood says, “Okay. Now what?” I needed to hear that. At some point Ren and Toby meet up. In this narrative I am Ren, just as I am Jimmy (it is no coincidence that they once were lovers, that Ren still pines for him, even though he pines for Oryx). I am clueless. I need medical attention. I need help navigating the weather and defeating the bad guys. I’m a self-obsessed, selfish, stupid puddle. Toby, help me grow up.

Goocha gets up in the morning and is full of the dickens. She feeds herself pretend food (fake potatoes and carrots are soooooo much better than real potatoes and carrots) and hops maniacally. Still not much of a cuddler, but a new favorite game is to run back and forth between Ryan and me, hugging us and yelling, “I LA BEE TOO!” or, for those who don’t speak Goocha, “I love you too.” She fills me with everything. She is everything. I think, Do it for her! Stop being so depressed. Change. Change everything. If I could afford to make those superficial changes I would. I’d love to pierce my nose again, dye my hair, get another tattoo. But real change has to come from within. I need to stop hating myself. Duh. When I cry, she cocks her head, baffled, and stares with wide eyes. She used to point her finger and sternly scold me in gibberish. She’s tougher than me. Now she’s starting to understand, she’s starting to really see me as separate from her. Not only do I have my own desires and will, that she knows and already has little patience with, but now I’m someone who owns things, someone who feels things outside of her. I can’t teach her these habits. I know she’ll experience sadness, and probably even self-loathing, but I want to teach her to cope better than I am. I still look to art, but I’m not creating. This is all I’ve written in two months. I need to learn time management. Those few precious hours I have to myself need to incorporate art, exercise, and self-care. I need to learn how to do that. I don’t want her to ever think, My mom is pathetic. This is how I feel. Pathetic. I wanted coddling, nursing, help. Honey, fix me, hug me, love me. But I don’t need an enabler. Obviously. Vicodin is an enabler. I don’t Toby, not that Toby would be an enabler, she would have little patience for me. I need to be Toby. I need to be Zeb. I need to get shit done.

But first I’m going to crawl inside this hole and sleep…

“Man was born free, and he is everywhere in chains.” Rousseau.

Let’s get back to nature. Civilization sucks…

MaddAddam was long awaited but I’m so glad I didn’t have to. Finally everyone, all the survivors are together. They’re rebuilding, satisfying that perpetual narrative itch I have for the raw-survival-in-nature trope. (This is what drew me to Lost, but lets not now or ever discuss Lost.) By this point I’ve realized what I was doing: that this depression wasn’t going to go anywhere until I finished MaddAddam, until I left this world and came back to my own. To my delight, Atwood stayed with Toby and gave us everything we wanted to know about Zeb, the sexy rebel gardener with a dark past and a knack for surviving. He’s crass, large, and highly intelligent, a kind of hacker-extraordinaire alpha Macgyver. Like Toby, I fell in love with him.

Back in reality, surviving equals thriving, not simply breathing. I wasn’t surviving. So I avoided blogging. But that isn’t the whole truth. I began this blog with the confessional in mind. It’s the Catholic in me, the exhibitionist in me, the way I look up to Kate Zambreno and Dodie Bellamy and Roxane Gay among others. I wanted this blog to be my personal narrative woven into, creating, revealing my perspective, my lens, my raison d’être, the when, why, what, how I deconstruct. Then I caught wind (or rather read her loud complaints) that my mother-in-law was reading my blog. Of course I anticipated people I know reading my blog, but given my mood, and that my mother-in-law deeply despises me, I felt exposed, critiqued, laughed at. One needs to appear strong in front of adversaries. To be hated so much gnaws at you, and while I’ve gotten used to it, mostly, sometimes I’m still bothered. My insecurity increased. My inkwell ran dry.

I no longer wanted to be seen.

I want to be seen again.

On the Edencliff rooftop, they don’t call it depression, they call it a fallow state.

Fallow: 1. plowed and harrowed but left unsown for a period in order to restore its fertility as part of a crop rotation or to avoid surplus production. 2. Figurative: inactive : long fallow periods when nothing seems to happen. 3. (of a sow) not pregnant.

Solutions are found, among the gardeners, with hallucinogenics. They take some mushrooms and perform an Advanced Meditation. I can’t take mushrooms anymore because of the migraines, but I can try and meditate and think and write about what to do next. I’m unsown, inactive, and not pregnant (literally, thankfully, but I mean that my language is no longer pregnant). Poetry eludes me. My ideas seem meek and paltry. Pathetic. That word, rolling about the page. It feels good to be back, but I’m not fully here yet. I have dips. I wane still. But it’s getting better. Maybe that was a kind of postpartum, maybe it was from a sudden drop in serotonin, maybe I’m terrified of getting off of Vicodin, or of any real change in general. I crave it though, and fortunately, it’s happening, whether I’m ready or not, whether I like it or not.

Every year, around my birthday, I freak out. Often, it’s about my failings, anxiety about my crushing ambition, but mostly, it’s about my inevitable death. My Thanatophobia is why I bury myself in books. Bound and bracketed texts comfort me.

Every year, around my birthday, I freak out. Often, it’s about my failings, anxiety about my crushing ambition, but mostly, it’s about my inevitable death. My Thanatophobia is why I bury myself in books. Bound and bracketed texts comfort me.

Ernest Becker in The Denial of Death writes, “The real world is simply too terrible to admit; it tells man that he is a small, trembling animal who will decay and die. Illusion changes all this, makes man seem important, vital to the universe, immortal in some way.”

The world is simply too terrible to admit. Look at Syria. Look today. It’s not fair. It’s unworldly to me, unfathomable. When Ryan writes about Syria, when he talks about it, none of our friends respond. People push Syria into a deep pocket, away from their to-do lists and their lunches and bowel movements. I’m no different. I look at the computer then look at Aria, empathy overwhelms, then I cry. For some reason when I cry Aria runs over, finger pointed, and speaks Aria in a stern manner. “Stop crying,” I think she says and I am once again thrust into here, safety, the couch, chopping fake vegetables. Kids really do perpetually shove you back into your everydayness. Anytime you have an authentic moment, revealing your being-towards-death, there they are, coloring the walls, demanding your immediate attention less you have permanent blue streaked walls, which I do now. I should really look up how to remove crayons. You’d think they’d all be washable. I mean, duh.

Writing is words that stay.

She’s leaving her mark. I get it. I applaud it. I do the same.

Writing makes me feel immortal. Not simply because my texts will remain after I’m gone. The universe is expanding, for one, all will be lost, including Shakespeare. Also, my work could disappear from fire, technical mishaps, lack of interest. No, writing, for me, creates importance, gives me the illusion of control, gives me the illusion of immortality through the chain of readers reading, readers reading to write, which is the point of it all: to write texts that make other people want to write texts.

So I insert myself as author, as character.

Through my work I am my own mother. My work – myself – is my child.

Like my home, my work is an extension of myself.

Unlike my daughter.

Who is Aria to me?

She is a person who is not me.

We procreate to live forever. We procreate because we will die.

But the show must go on.

Like thoughts,

Ceaselessly,

Cruelly.

Madame Bovary dies, and still, the book goes on.

I can’t fucking believe the universe is expanding. Life was much simpler when the sky was Heaven, not space. As a result, space frightens me. Ryan doesn’t understand that.

When I think about his death, I think about madness. The kind of grief that consumes totally. Filled to the proverbial brim with blackness, nothingness. I don’t know which is more terrifying, my death or his. The thought of Aria’s death is too hideous to contemplate. Horrors cross my mind every now again, of course they do. I fantasize about someone kidnapping her at the grocery store. I then imagine I’m Leela and beat the living shit out of those people, saving my child, killing the bad guy, turning my husband on immeasurably.

I can’t believe that everyone I know and love will die.

Maybe it’s because I grew up Catholic, and that my parents are incessant optimists, but I feel as though immortality is somehow around the corner. That three generations from now we will have found the scientific secret of youth and eternal life. That this dread, this fear, the anxiety and the terror will all be over.

But I will have missed out.

I’ve never been swept away by a crowd – merged into mob mentality.

I was always uncomfortable at pep rallies then political rallies or protests, or – especially – in church. When the priest says, “Let us lift up our hearts to the Lord,” and everyone responds, “It is right to give him thanks and praise.” I was always creeped out. Religion is a palliative. Freud saw it as a weakness, an inability to cope with the torments of obliteration, a passivity that defeats our creative urges for more life.

Becker quotes Otto Rank:

[Surrender to God] represents the furthest reach of the self, the highest idealization man can achieve. It represents the fulfillment of the Agape love – expansion, the achievement of the truly creative type. Only in this way…only my surrendering to the bigness of nature on the highest, least- fetishized level, can man conquer death.

I take this as a personal challenge.

One can only achieve peace if one gives oneself over to the great public dream of eternal life?

I scoff.

There are no atheists in fox holes. I think Christopher Hitchens has disproved that.

Art is not designed to quiet the soul, to be a pacifier – it is designed to enlighten, ennoble, to strengthen, fight, and prepare. To feel God inside your veins through the act of creation is an addictive high that cannot (as gravity dictates) last.

That does not mean to give up and give in to a god because he is a better artist than you.

And giving in by way of taking Pascal’s Wager will not eradicate the doubt deep in your belly. That specter of impending nothingness will never fully dissipate.

Art is the only way I know of coping with that.

Art is the only place I know of where a woman is accepted. Where she can be herself.

“Write from your body,” Cixous says. Write with your body, write in white ink, mother’s milk. Your work, your collected body of work, are your babies, is your body.

Through writing I can pretend I’m not shackled to my carcass; this loathed, bloated, exhausted carcass.