This

This book blog post is not about Beckett at all…

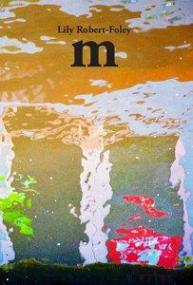

The inimitable Lily Robert-Foley, best friend extraordinaire, wrote a book, m, that, while a text in and of itself, is more of a transmission: the revelation of, or commentary on the space between Beckett’s L’Innomable and The Unnamable, which was first written in French and then translated into English–Beckett’s native language–by the author himself.

In between these two texts beats the third text, which Lily describes as:

the space between translations: An invisible text that emerges from the rupture/conjunction of the languages. In the poems, the third text is treated as a creative space that produces text (writes, figurates, allegorizes, critiques &c.). In this sense, the following “poems”/“notes” may or should be considered a sort of translation or reading of the third text of Beckett’s novel. (Introduction)

Inside this third text the chasm beneath our feet rips open: it invites: l’appel du vide.

At best, here, I offer my interpretation, my translation of Lily’s translation of Beckett’s autotranslation.

The whole point of this blog is to collapse the space between reader and text. To expose the reading process. This is what Lily accomplishes in m.

Like a road, or a poem, m is a metaphor. This is an experimental book of poetry, so the page can be intimidating, especially if you don’t speak both French and English, as she quotes Beckett in one language then gives the equivalent passage in the other, after which she then performs an exegesis, mostly in English, but also in French. Her words are ghostly, printed in gray (Beckett’s are in black). They give the illusion of hovering between the texts, as though she were reticent to pin them down, because they don’t belong in a book, they belong to The Unnamable, the texts: L’innomable/The Unnamable; but also as a concept: that thick, viscous, nebulous abyss that is everything and nothing. But even still, that’s not right as the third text deconstructs the stuff of the unnamable.

The third text:

does not locate the [third text] in an unnamable space but tries to determine the matter or substance of the unnamable, divide it, bust it, burst– (160/383)

But my understanding is that zero multiplied by anything will always be zero.

This is also what I mean when I say that I struggle with nihilism.

It’s all Zeno’s Paradox to me.

The ideal of the unnamable or the untranslatable refers to language that has no other, either because it is no language or is only language. The 3-text reading (a poetics of self-translation) is the confluence of these poles, or rather renders them irrelevant (since they are the poles of language-that-has-no-other in a system of language based on same/other). (74/331)

All thought is made up of language. To quote Wittgenstein: “The limits of my language are the limits of my mind. All I know is what I have words for.”

Now, what about the fact that I only speak English?

The text is already bilingual, even if you only read half of it. Holes where the other half of the text comes through (removable discontinua). The penetrable intimacy of language, or queer the gender, its enveloppable intimacy. It’s pour, poor, pore, porous, aporia. Like this book, some things you might not understand because they are in another language or situated in an obscure discourse, but it’s ok, like a self-translated text, you only read half, no text is a totality anyway. (90/340)

Language is gendered, it’s phallogocentric. Meaning, meaning tends to privilege the masculine: the throbbing, glittering Signifier.

Derrida’s deconstruction of speech and writing is bound to the word parole (untranslatable as speech). Parole is fatherly. Straight, from the soul, pure breath of spirit. (31/305)

Also, language is heterosexual (it’s all about the binary, baby). And holy. It is our most sacred tool.

To quote Sappho: “Although only breath, words which I command are immortal.”

Once upon a time, words were considered “truths.” There was no difference, no space between signifiers and what they signified. Deconstruction has taught us that language is a game of différance. Language is slippery. Words have meanings only because other words have meanings. Something only is what it is because of what it is not. These small differences make up the constellation of words and meanings, which means, no word can contain any essential meaning. Language is empty. Meaning will always be deferred through an endless chain of signifiers.

If this sounds confusing, translation only compounds the complexity.

The third text reproduces the rapports de signification internal to one language, but splays (écart) them out across two languages. Each language acts as a set of signifiers representing the other set of signifiers as their signifieds, and those signifieds acts as signifiers signifying the other set of signifiers as their signifieds. Endlessly, hall of mirrors, referring to each other. (30/305)

The third text is not gendered (from here on out, like Lily, I shall refer to the third text as “3ext”), it’s monstrous, “something so horrible I can’t put it into words.” Immediately, I think of the familiar yet foreign monster lurking in the apparently boundless basement in The House of Leaves. That entire metaphor, for me, is a metaphor for the divine and uncanny 3ext.

Familiar yet foreign:

Repeats, ça me dit quelque chose (literal traduction: that means something to me = ring a bell…)…

an in-between space that is also rhetorically beyond, too far, too close. (177/393)

The 3ext is always foreign to itself, a refugee, never at home, forever invaded, a colony of a state that doesn’t exist, where the native is the mold of the foreign. (181/395)

Or more succinctly:

The poetics of self-translation is the becoming foreign of the native and the rendering native of the foreign. (46/314)

The reason I’m quoting so much, and mostly quoting passages that “define” the 3ext is because once you’ve grasped some basic understanding of this space, this space stolen, as it were, from Beckett, you can fly with Lily through her poems, which are not as complicated as this blog would lead to you to believe: they’re playful and they’re funny. And yes, while Beckett is funny (think Patrick Stewart’s and Ian McKellan’s interpretation of Waiting for Godot, which was hilarious), this “book is not about Beckett at all.” It’s about the 3ext and it’s about Lily: the author: the author who was the reader, who translated back and forth, and quips: “Negligent writer seeks cop editor.” And, “the opposite of madness is raisin.”

Now, indulge me: “raisin” is obviously a pun on “reason” and more poignantly the French translation of reason, “raison.” But on top of all that, a grape can survive one of two ways, it can either become wine or a raisin. A raisin is wine that never was. The god of wine is Dionysus, who also represents pure madness. If wine is madness, then a raisin would be its opposite. Wholesome kids’ snack versus bacchanal orgy. Clever, and fun if you’re a super nerd like myself and love unpacking seemingly random symbolism to stitch together some type of chaotic whole that nurtures as it’s digested.

The text of m is hysterical, it goes from one subject to the next. To the reader, it’s as though she pulls a random Beckett quote from the hat then creates a palimpsest on his words. She inserts herself. Fucking the space between, the now stolen space between, Beckett’s work becomes othered. We forget that she’s siphoning off of him because she’s not parasitic, she’s a pioneer, as all us thinkers and readers are, but she’s literally marching through the frontier, conquering it, and passing it along. Herein lies the oscillation between hermeneutic discourse and poetic discourse. Lily once said that there is nothing more transgressive than to interrupt/surprise the father in the speech act. Herein lies another metaphor for the 3ext as Lily is constantly interrupting Beckett.

Good thing the author is dead.

But let’s not go there.

Long live the author!

(Especially Lily.)

Let us fly:

the meaning, value, weight, comes together while the material, phonemes, morphemes, choses, pull apart, as in the making of mountains : desire, love, reaching out to the other, Michelangelo’s Adam, bigger on the inside than on the outside : an analogy of infinite regress in ethics : the more I know you, the more mysterious you become to me, the more what I thought was my knowledge of you is eclipsed by my love for you : (132/366)

Wait! Bigger on the inside than on the outside?

Oh, the politics of interiority versus exteriority!

Boundaries are for suckers.

To explore the space of the self is truly the final frontier.

Speaking of…

Today Anaïs Nin would’ve been 111.

Let’s look at a full “poem.”

« Mais lessons tout ça »

« But enough of this nonsense »

Let’s leave, move away from, this language that doesn’t mean anything, go towards sens, follow a road full of metaphor, Jiji. (62/324)

Jiji is the eponymous character from Lily’s roman à clé, Jiji (forthcoming from Omnia Vanitas Review), which, though loosely autobiographical, is also an experimental ride, written progressively in code, so that by the end, the text appears unreadable. Because so much of the love story is lost in the translation, because one can never truly know the Other, because this story needs to be encoded in order to be told.

But inside m, the reader is not privy to Jiji–not yet–so the reader may not, and probably doesn’t know of Jiji, because they aren’t coming to this book of poetry with my perspective of privilege. Remember: “Like this book, some things you might not understand because they are in another language or situated in an obscure discourse…”

When the author others herself, who is reading? So here, the subject writes herself as other-object. She makes the her-in-the-page perform, read, translate the emptiness that creation can eradicate. Suddenly all characters are water. This can happen at any time. I love that about her work. This is Lily. She mostly writes ergodic literature; “nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text….[T]he reader…must participate actively in the construction of the text.”

Experimental, ergodic, hysterical, wonderful literature.

Since the 3ext resists organized hermeneutics, I will just leave you all with this aphorism:

Facebook is phatic-phonetic, has replaced main street the way television has replaced the novel. (110/352)

Then, because I love her, and I want you all to love her, I’ll leave this, then leave you: